The nature trails themselves allow for an easy hike. For the most part they're flat and there is shade at various points. The trails are well maintained and some of them have signage posted to identify the plants for you. Benches have been provided all along the way. There is a variety of wildlife to see while hiking. One of the boardwalks crosses over an alligator lagoon where young gators can be spotted sunning themselves on the bank. Birds such as blue herons, egrets, pelicans, and many, many others can be seen.

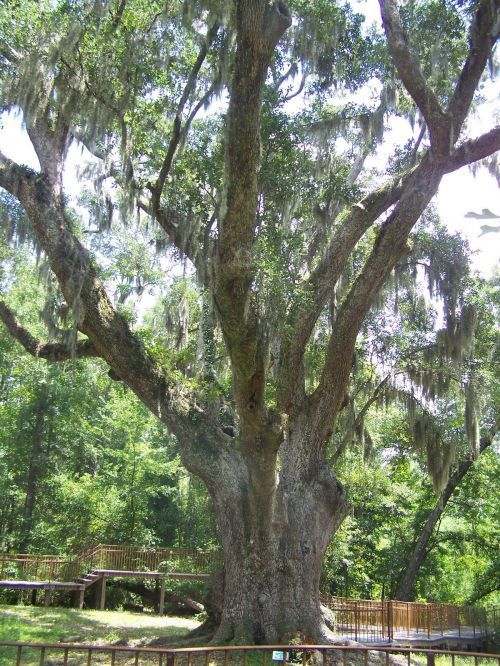

The Historic Village Point Preserve is home to one of the largest and most historic live oaks in Alabama. This giant tree, which is 95 feet tall, with a circumference of 28 feet, was a landmark in the eighteenth century: it is shown as a survey line marker in the original Spanish Land Grant survey map of 1787. How did Jackson's Oak get its name? According to local traditions, General Andrew Jackson made a speech to his army from one of its massive limbs, while he was enroute from Pensacola during the War of 1812. Protection and preservation of this magnificent live oak is a top priority of the City of Daphne and the Village Point Foundation. An observation platform was carefully constructed around the tree, to offer an excellent view, and to provide protection from pedestrian traffic, which research has shown would eventually compact and erode the soil, causing root damage to the tree.

Daphne's Treasure- Treasure! An exciting word that immediately captures our interest. Visions of pirates preying on majestic sailing ships filled with gold, silver and fabulous jewels form in our minds. Then, sailing to a desert island or a fortified lair, the pirates bury their ill-gotten gains in order to safeguard them. We dream of discovering long buried or forgotten treasure that has just been waiting for some fortunate person to discover it. Although colorful legends and local stories tell of the infamous pirate Jean Lafitte sailing on our bay and hiding under nearby bluffs, the treasure found in the Village Point Preserve is of another sort. The Preserve, Daphne's newest park, is rich in local, national, and world history. Some of the earliest inhabitants of North America lived and roamed on this land. Europeans explored and founded colonies here. At times, they brought their differences and even wars to this area. Early settlers and immigrants carved out new homes and lives on this land, as thousands were doing in what was to become the United States of America. We know this because evidence of Indians, Spanish, French and English people has been discovered in the park area. It is unknown how much more is to be discovered, but the possibilities are endless!

Since the Village Point Preserve was founded many discoveries have been made. Digs and research have indicated there is still much more "buried treasure." In fact, the surface has barely been scratched. There is so much more to learn and see. We study our past to understand ourselves and to shape our future. We preserve and safeguard our natural treasures so future generations can do the same.

This area, west of the highway to the shore of Mobile Bay, south to Yancey Branch and north to Bay Front Park Drive, has been a natural campsite, meeting place and rest stop, dating back as early as 1500AD. Artifacts, arrowheads, clay pottery, and implements were excavated here near burial sites of prehistoric mound builders. Native American tribes held large council meetings here and called this area the "Sacred" or "Neutral Ground." Pioneers built log cabins here; several of these family names remain prominent within our community (D'Olive, van Iderstine, Carney, and Starke). Between 1670 and 1763, French troops from Fort de la Mobile stayed here. The Village became important as the eastern terminal of ferry traffic as people and cargo moved between Mobile and Pensacola. A French colonial village flourished here until it was destroyed by Yellow Fever in 1820. In 1778, one of the Village residents, the cunning diplomat Alexander McGillivray, gained notarity by taking advantage of his Scotch-French-Native American lineage and simultaneously serving his "Creek Confederacy" while drawing salaries from the governments of Great Britain, Spain, and the United States. The Spanish named this area La Aldea (the Village). Between 1780 and 1813, Spanish cavaliers paused here on their march north to Spanish Fort. In 1781, an important Revolutionary War skirmish took place here between British and Spanish troops and virtually forced the surrender of General Charles Cornwallis.

In 1814, General Andrew Jackson visited the Village (verified by one of his drummer boys and former resident of this area, William Ramsey Yancey). It seems that the British troops were freely using the Spanish port of Pensacola despite multiple protests by General Andrew Jackson. Although not officially at war with Spain, Jackson took the responsibility of an attack and marched from New Orleans through Mobile to the Village where he bivouacked his 3000 soldiers en route to Pensacola. On that occasion, Jackson climbed the limbs of a magnificent oak draped with graceful silvery moss to rally his bedraggled troops with a speech. This oak tree is believed to be alive and well in the Village Point Park and has been preserved as Jackson's Oak. The route that Jackson subsequently followed across Baldwin County to Pensacola has long been known as the Jackson Trail. When Jackson and his troops arrived in Pensacola, the Spanish government wanted to negotiate, but Jackson had not come to talk, so the British blew up the fort, boarded their ships and put out to sea.

Near Jackson's Oak is the D'Olive Cemetery, which has the oldest tombstones in Daphne and is surrounded by a beautiful iron fence. It is the resting place of Louis D'Olive (1769-1841); his wife Louisa Le Fleur (1782-1840); his sons Marone (1803-1830) and Mederick (1812-84); his daughter Louisa ( died 1864) and Louisa's husband, Major Lewis Starke (1799-1872). Some of the graves are bricked up several feet and the stones on top are placed upright instead of flat. Inscriptions are in French. Another unusual feature is a double grave for a mother (Anneys Laurendin) and her 18 month-old son (Edward); both died in March 1837. During the Civil War (1861-1865), Confederate soldiers camped at the Village. In 1865, the Union fleet landed reinforcements of soldiers at the Village piers during the campaign to capture Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley.

The land itself is unique and without equal in this area. Natural treasures abound. State champion trees, unsullied wetlands, streams, and undeveloped woodlands are just a fraction of the wonders contained in the Preserve. A treasure that no price or value can be put on, and the Crown Jewel of the Preserve is the unlimited public bay access. Daphne citizens and visitors alike for generations will use and enjoy one of the very few remaining public beaches on Mobile Bay.